With my favorite cowboy hat. 1955 RCA recording of Swan Lake.

I recently came across a few boxes I hadn’t opened in fifteen years or more. They contain the last vestiges of childhood memorabilia that I can’t quite let go of: my Tonka fire truck and car carrier, Creepy Crawlers kit with half filled bottles of Plastic Goop, a 1955 RCA recording of Swan Lake. I know—one of these things is not like the other ones. Truth be known, I own a few of copies of this album, having purchased them on eBay over the years.

As a kid, I would pull an armload of albums from the record cabinet and lay the covers out across the living room floor. I could spend hours staring at the pictures, the typography, and the wonderful color combinations. Small wonder that I worked at a record store in college, or that I went on to study graphic design. Yet, out of all the albums my parents owned, this one struck me like no other.

The cover is perfection: a ballerina lies on her back, shoulders pressed to the floor, her elegant legs pointing straight above. Her toe shoes, a pale blush color, land between the first and last name of Leopold Stokowski, and lead your eye to the title of the album. The entire composition floats atop the most sublime pea green background.

I recently learned that Andy Warhol designed the cover (his 15th) and the book that’s stitched inside, with fanciful pen and ink sleeve illustrations to which I was drawn, and the hand-masked photographs that suggest a body of work yet to come.

In retrospect it all makes sense—my affinity for the colors of Necco Wafers, my Father’s copy of East of the Sun and West of the Moon with Kay Nielsen’s exotic illustrations, Henry Vandyke Carter’s engravings from Gray’s Anatomy, Spirograph.

I asked some designers, illustrators and artists whose work I admire, what visually influenced them as children. Some answers were unexpected, some fitting—all were interesting.

* * * * * * * * * * *

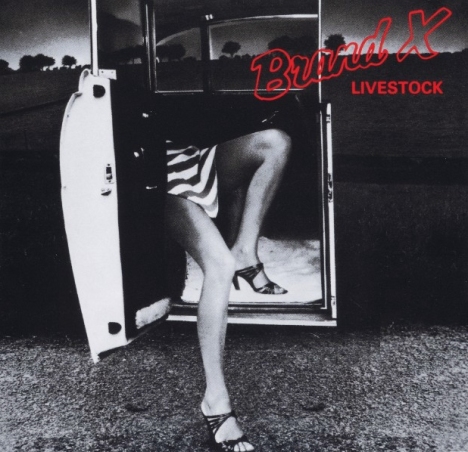

Vaughan Oliver. Album cover for Asobi Seksu.

“I’m a cheap date. Just give me a bit of type and an image to work with—I can find satisfaction in that.” VAUGHAN OLIVER’s name is synonymous with the evocative, often moody post-punk art of the 4AD label. For nearly 30 years, the British born designer has struck a tense balance between gritty texture, elegance, and a fine art sensibility, creating palpable atmospheres on which to place his highly stylized typography. His 23 Envelope and v23 Studio collaborations, with the likes of Nigel Grierson and Chris Bigg, have defined a genre through artwork created for artists such as The Cocteau Twins, This Mortal Coil, The Pixies, Lush, Robert Fripp, David Sylvian and Dead Can Dance. Vaughan has authored several books including This Rimy River and Visceral Pleasures, and his work has been included in the collection of The Victoria and Albert Museum.

Whereas all other responses were written, Vaughan sent the preceding nine images as his inspirations: 1) Instruction booklet for Ekco Radio, 2) Illustration plate from Ladybird Marco Polo, 3) Cigarette card of Apollo astronaut food, 4) Terrapin: Curious Member of the Tortoise Family, 5) Signed cigarette card of David McCallum in The Man From U.N.C.L.E., 6) Doilies, 7) Cigarette card of more Apollo astronaut food, including Salmon Salad, 8) Book plate titled Youngsters of Switzerland, 9) Radio tube value table.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Woody & Robert Pirtle, 1949. Poster for The Letter Y.

Woody & Robert Pirtle, 1949. Poster for The Letter Y.

Texas born WOODY PIRTLE epitomizes concept driven, illustrative economy in design. The son of a corporate Penzoil pilot, he spent his formative years in Louisiana and entered the workforce schooled in fine art. By the late 1980’s, Woody’s work boasted numerous awards, he was voted into membership of the Alliance Graphique Internationale, and was invited to join Pentagram as a partner in their New York office. There he instilled his creative wit into identities, posters and corporate communications for clients ranging from Fine Line Cinema to The Rockefeller Foundation, from IBM to Pantone. In 2005, Woody re-established Pirtle design. He has served on the AIGA Board of Directors, has taught at The School of Visual Arts, has lectured extensively. His work graces the collections of MOMA, The Library of Congress and The Victoria and Albert Museum, just to name a few.

“I was mesmerized by the “test pattern” on our B&W television set as I waited impatiently for one of the few programs to be aired at 4pm in the afternoon – Howdy Doody. I was also intrigued with the odd bird on the Kiwi shoe polish tin, not to mention the brightly colored circles on the Wonder Bread packaging. And then there was my dad’s 1949 maroon Ford Coupe…”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Margo Chase’s logo for Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

“I got started by accident really. I was a biology major in college, studying to be a veterinarian.” In 1986, fresh out of grad school with a degree in Medical Illustration, MARGO CHASE set up shop. Her abilities in hand drawn typography, combined with a healthy dose of Gothic romanticism, landed her some highly visible design for the music industry. Warner Bros, Virgin, Capitol Records, sought Margo’s unique approach in developing logos and packaging for artists that included Prince, Madonna and Cher. These successes lead to title design for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, packaging for Kama Sutra products, as well as a line of celebrated font designs. These days, when she’s not engaged in competitive aerobatics, Margo marries her analytical aptitude with her right brain sensibilities, focusing on branding, positioning and problem solving for clients such as Target, Kemper Snowboards, Mattel and Cartoon Network.

“An important early influence was my mother’s calligraphy work, her books and all her unusual pens and nibs. She wrote beautiful letters and I used to watch her write out the programs for church in beautiful script. At some point I was given a set of lettering templates and engineering tools – compass, ruling pens and other mysterious objects – all fitted neatly into a wooden box. It must have been my father’s from engineering school. I had no idea how to use them. But I loved to take them out and play with them and them put them all back into their perfectly shaped slots. My grandfather’s hobby was photography. He had a darkroom in the garage where all kinds of strange-smelling operations happened in the dark. When we visited them in the summer he would sometimes let me in to watch. When I grew older he taught me to process film and make prints and enlargements. I loved watching the backwards/upside/down/negative images magically transform into scenes or portraits that I recognized. My family is full of creative people so the influences were all around me. It isn’t surprising I wound up a designer.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Mark Hess. Prince Pasta Sauce: Regular & Chunky.

If you’ve ever looked at Time Magazine, leafed through the pages of Forbes, or placed postage on an envelope, you’re probably familiar with the work of MARK HESS. The Michigan raised illustrator, who rode rodeo bulls by the age of 10, began his career as a painter in 1975. By the age of 19, Mark landed his first of 17 cover illustrations for Time Magazine. Not to be outdone, Newsweek and Forbes followed suit, enlisting Mark’s witty references to culture past and present, all wrapped in an editorial twist. His postage stamps, including the Civil War and Legends of the West series, total 46 to date, and The Smithsonian currently boasts ownership of 41 of his pieces.

“As a child I had many visual influences that probably affected my taste and style. Some I can remember and some I’m sure are just part of my subconscious; rearing their ugly little heads when I least expect them, pushing me this way and that. I’ve actually been a bit of a child most of my life (or is that childish?), but I assume you mean a child as in before the age of 12 or so. So let me see what I can think of off hand…paint by number paintings, Rat Fink models by Big Daddy Roth, suburban Detroit, Bozo, match book Learn To Draw ads, race car graphics, Shari Lewis & Lamb Chop, Playboy, Tom Terrific, Grandma Moses, Topo Gigio, Vargas pin-ups, record album art, murals in post offices, folk art, TV, Diego Rivera (a painting in the Detroit Art Museum), my incessant need to draw and represent the world around me (does “me” count?), barber polls, Robbie the Robot, funky drawings by other kids in grade school, bad clown paintings my grandmother liked (especially by Red Skelton), John Gnagy (TV art teacher), Highlights Magazine, sexy women, painted magazine ads (cars, cereal, Xmas, GE, candy, gas, tires, trains, boy scouts, fashion, SOS, Mr Clean, etc.), Saturday Evening Post, Mad Magazine, Time Magazine covers (all paintings), Elsie Borden, Soupy Sales, stiff, pointy bras, Creepy Magazine, N.C. Wyeth illustrations, packaging (Toni the Tiger, Mr. Clean, Morton Salt, Quaker Oats, etc.), Godzilla movies, Life Magazine, Norman Rockwell, Sci-Fi books. Ok, so some of these may not seem like visual influences (like Soupy Sales: he had crazy art on the walls), but I can explain every one. I think Picasso said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up. Easy, never grow up.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Mick Haggerty. Album cover for David Bowie’s Let’s Dance.

MICK HAGGERTY moved from England to Los Angeles in 1973, became an accidental neighbor to artist Ed Ruscha, and launched headlong into a career designing iconic album covers ranging from David Bowie’s Let’s Dance and The Go-Go’s Vacation, to Supertramp’s Breakfast in America (with Mike Doud), and The Police’s Ghost in the Machine. Not surprisingly, the demand for his beautifully executed, high concept work led to Mick’s direction of videos for the likes of Public Image Ltd., King Crimson, Sting, The Violent Femmes, and The B-52’s. Today, Mick concentrates on his personal paintings and serigraphs, which are equally imbued with vaguely familiar cultural references, bold concept and graphic angularity. Shephard Fairey recently referenced Haggerty’s Jimi Hendrix poster and The Police’s Ghost in the Machine album cover as being two of his influences. Both are now framed and hanging in Shephard’s studio. (I had the pleasure of studying with Mick in 1985, when he served as a visiting professor at Art Center College of Design.)

“My bedroom wallpaper featured heavily in my dreams, bruise colored roses on pale blue as if imagined by Adolph Gottlieb…..The Beano’s Bash Street Kids …. Max and Dave Fleischers‘s Popeye… books of World War ll photographs, especially the explosions….the instructions in plastic model kits…and of course Bill and Ben the Flowerpot Men….”

* * * * * * * * * * *

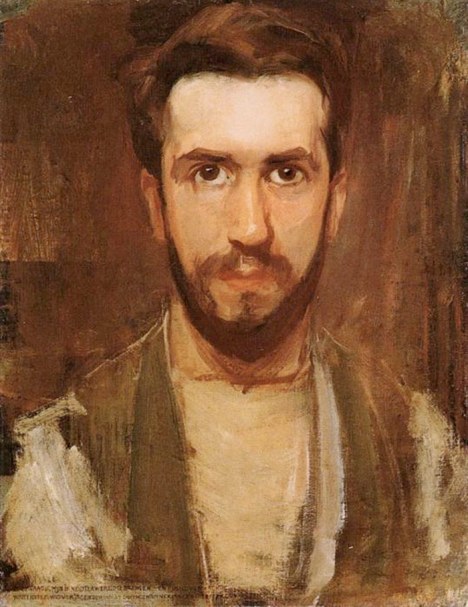

Plilip Burke and identical twin brother Paul. Portrait of Tupac Shakur.

You know his work—the fauvist, caricatured, oil portraits that get the good real estate in Vogue, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, New Yorker. PHILIP BURKE, who grew up in a Buffalo, N.Y. Irish Catholic family with four sisters and six brothers (one of whom is his identical twin, Paul) employs his Buddhist sensibilities when painting celebrity musicians, politicians, actors, comedians. Burke’s use of distortion is intended to capture the essence, the intensity, the presence of a subject, and not to ridicule. The self-managed illustrator/artist averages eight to ten paintings a week, in which he draws from a broad array of influences that include Picasso, Francis Bacon and Ralph Steadman. His work is owned by many of the celebrities he has depicted, and he has been recognized by The Society of Illustrators, The Society of Publication Design, Communication Arts, and The Art Director’s Club.

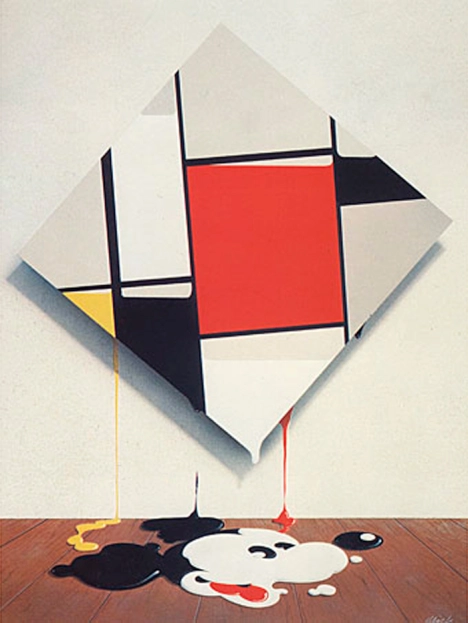

Philip’s influences were, “Disney animation circa 60s—specifically the classic Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck—and the Saturday and Sunday funny papers!”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Archie Ferguson, 1979. Book Cover for Nick Hornsby’s About a Boy.

HarperCollins art director ARCHIE FERGUSON has a knack for the elegant solution—the one that communicates the maximum through his use of the minimum. He’s the guy who designs the covers that bring a smile to your face as you nod your head in the bookstore. “As a visual and analytical person, I don’t think I’ll ever stop seeking meaning or connection between things.” Archie graduated from the School of Visual Arts (where he studied with Paula Scher, and where he currently teaches) in the late 80’s, and began his career at Random House. Over the past couple of decades, he has designed between one and two thousand book jackets, has worked at Knopf (as a member of Carol Devine Carson’s dream team that also included Barbara de Wilde and Chip Kidd), Time Books, Pantheon and Schocken. His work has been featured in prestigious design annuals, and is the recipient of numerous awards.

“Think the reason I liked Velveeta Cheese so much was because of the color. Had a penchant for the sets and fashion of The Dating Game, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, and The Sonny & Cher Show. And of coarse The Brady Bunch. Kiss had really cool album covers and who could forget The Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers, and Paul Scher’s cover for Boston. My mom always dressed me in blue.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

J. Otto Seibold. Mr. Lunch Takes a Plane Ride.

J. OTTO SEIBOLD, illustrator of the upcoming Chronicle children’s book Other Goose, is probably best known for his characters Mr. Lunch and Olive (the Other Reindeer). The self-described “F+ student” worked initially as a Bay Area architectural designer. Then, in 1987, packing the full power of a three-year-old 128k Mac, J. Otto (pronounced like the famed Veronese architect and fresco painter) hung out his shingle as an editorial illustrator. Flying cross-country with his dog, Dexter Lunch, J. Otto brainstormed his first storyline and began his foray into the stylized, witty, whimsical (think Joan Miro and Hieronymus Bosch meet The Jetsons—with animals) world of children’s (and discerning adults) books. To date, he has created some 17 books, often collaborating with wife and writer Vivian Walsh. Olive the Other Reindeer was animated for television—Olive being played by Drew Barrymore—and garnered a Primetime Emmy nomination.

“Sure… I remember the creek. The bridge over the creek. A train that went across the sky. And the book Mike Muligan and His Steam Shovel….oh, and the roll-out of Hot Wheels.” J. Otto has also cited Lego Building Blocks and Speed Racer as being formative influences.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Anita Kunz. Illustration of Roseanne Barr.

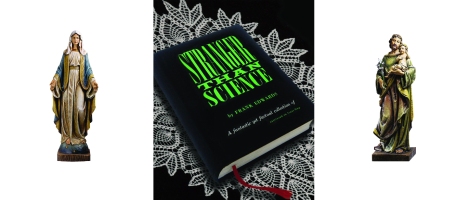

ANITA KUNZ, Officer of the Order of Canada (think: Mick Jagger being knighted), and one of The Fifty Most Influential Women in Canada—as named by The National Post—turns gouache and watercolors into conceptual portraits and editorial illustrations, steeped in social and political context. The highly collected, prolifically honored artist has illustrated better than 50 book covers, and has contributed her visual perspective to GQ, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair, not to mention Rolling Stone’s illustrated series of the History of Rock ‘n Roll. Having been powerfully affected by certain instructors during her education, Anita pays it forward whether lecturing at The Smithsonian, or teaching and leading workshops internationally.

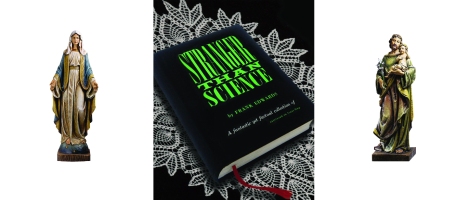

“Oh dear…I think I was kind of a spooky kid. I’d read books with names like Stranger than Science about spontaneous human combustion and stuff like that, and scare myself silly. And when we went to church (we did that back then) I’d watch the mouths of the statues and convince myself they were moving! Sheesh!!”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Barbara Nessim. “In Vision” from The Model Project.

BARBARA NESSIM put herself through Pratt, working as a fashion illustrator in the Garment Center. It’s no surprise, really—Barbara’s mother had been a clothing designer. Equipped with a degree in Fine Art and Illustration, she began what would be a pioneering career, at a time when few women worked as freelance commercial illustrators. Nevertheless, she parlayed her unique style into success, designing apparel and textiles. Then, in 1980, as many struggled to define what connection if any could be drawn between art and the advent of the computer, Barbara dove headlong into technology. Drawing upon her fine art mindset, she trailblazed a digital, visual vernacular that opened the doors of possibility, and continues to be a source of influence today. Barbara has served as an educator at the School of Visual Arts in New York, and at Parsons The New School for Design. Barbara has shown at The Louvre, is in the permanent collections of The Victoria and Albert Museum and The Smithsonian Institute, has graced the pages of Time Magazine and Rolling Stone.

“I loved black laced-up, low cut flat shoes, shoe store windows, black and white tile floors, dancing school costumes with all the sparkle, and Many Moons by James Thurber and illustrated by Louis Slobodkin.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Clement Mok. The Republic of Tea identity.

CLEMENT MOK is a household name amongst the early-adopter Mac faithful. The Vancouver born designer, educator, author and entrepreneur spans the worlds of design, experience, and technology, and played an integral part in the birth of Apple’s brand. Mok understood that brand was more than a mark, and designed a comprehensive experience that has become a standard for the tech giant. In 1988 he launched Clement Mok designs, focusing on design for software startups. With the advent of the internet, he morphed CMd into the interactive-based Studio Archetype which he eventually combined with global consulting firm Sapient. Today, half of Sapient’s $600M revenues are due to Mok’s expansion of design into the concepts of brand strategy, user experience, information architecture, and usability. His clients have included Adobe, Apple, American Express, IBM, Nintendo and UPS. He has received numerous awards, has served as CEO and as an advisor on the boards of many tech companies and colleges.

“My earliest childhood memory about art and design were grade school art projects on making Mexican God’s eye, color wool yarns wrapped in concentric bands on a cross. It was a 60’s hippy thing. I was fascinated by how color bands of different hue, tone and width can effect the overall appeal of the finished piece. Instead of making one, I probably made a dozen of them — raiding and depleting my mom’s yarn basket. That was perhaps the catalyst in getting me started in design.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

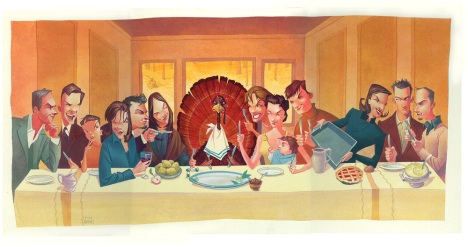

Socially conscious designer CHERYL HELLER, was encouraged in her love of cutting things with scissors—including the family’s maroon velvet couch. Pentagram partner MICHAEL BIERUT owes his love of design to Jon Gnagy’s television art lessons. Book designer CAROL CARSON loved listening to Peter and the Wolf, and would stare at the brightly flowered end papers of the book Walt Disney’s Surprise Package. BARBARA deWILDE, also a noted book designer, would copy art from Mad Magazine—whatever was funny.

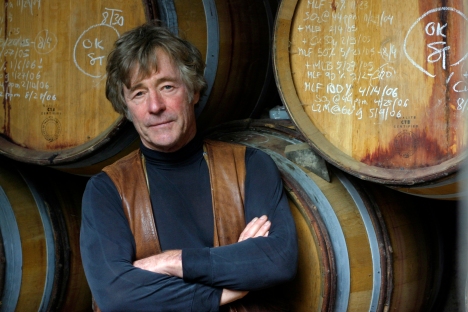

So, step into Mr. Wizard‘s Way-Back Machine, and tell me—what inspired you? In the meantime, I’ll decant a 2007 Domaine Solitude Chateauneuf du Pape. Talk about a shining example of the confluence of so many nuances and influences, this dark, perfumey Rhone boasts an herbal, beefy edge to the panoply of plum and cassis flavors and aromas.

Filed under: Chateauneuf du Pape, Design, Influences, The Fibonacci Design Group, LLC, Uncategorized, wine | Tagged: 4AD Label, AIGA, Andy Warhol, Anita Kunz, Archie Ferguson, Art Center College of Design, Art Director's Club, Barbara Nessim, Carol Carson, Carol Devine Carson, Chase Design, Cheryl Heller, childhood influences, Clement Mok, Clement Mok Design, CMd, Communication Arts, design influences, Envelope 23, Henry Vandyke Carter, Hess Design Works, influences, J. Otto Seibold, Kay Nielsen, Leopold Stokowski, Louis Slobodkin, Margo Chase, Mark Hess, Michael Bierut, Mick Haggerty, Pantone, Pentagram, Philip Burke, Pirtle Design, Pratt, Society of Illustrators, v23 Studio, Vaughan Oliver, Vivian Walsh, Wine, Woody Pirtle | 12 Comments »

Woody & Robert Pirtle, 1949. Poster for The Letter Y.

Woody & Robert Pirtle, 1949. Poster for The Letter Y.